Increasing the Power by Sharing It

Effective leaders in today's results-oriented K-12 world can seem like heroes, but the job starts with getting others to buy into - and take responsibility for - a larger vision

Effective leaders in today's results-oriented K-12 world can seem like heroes, but the job starts with getting others to buy into - and take responsibility for - a larger vision

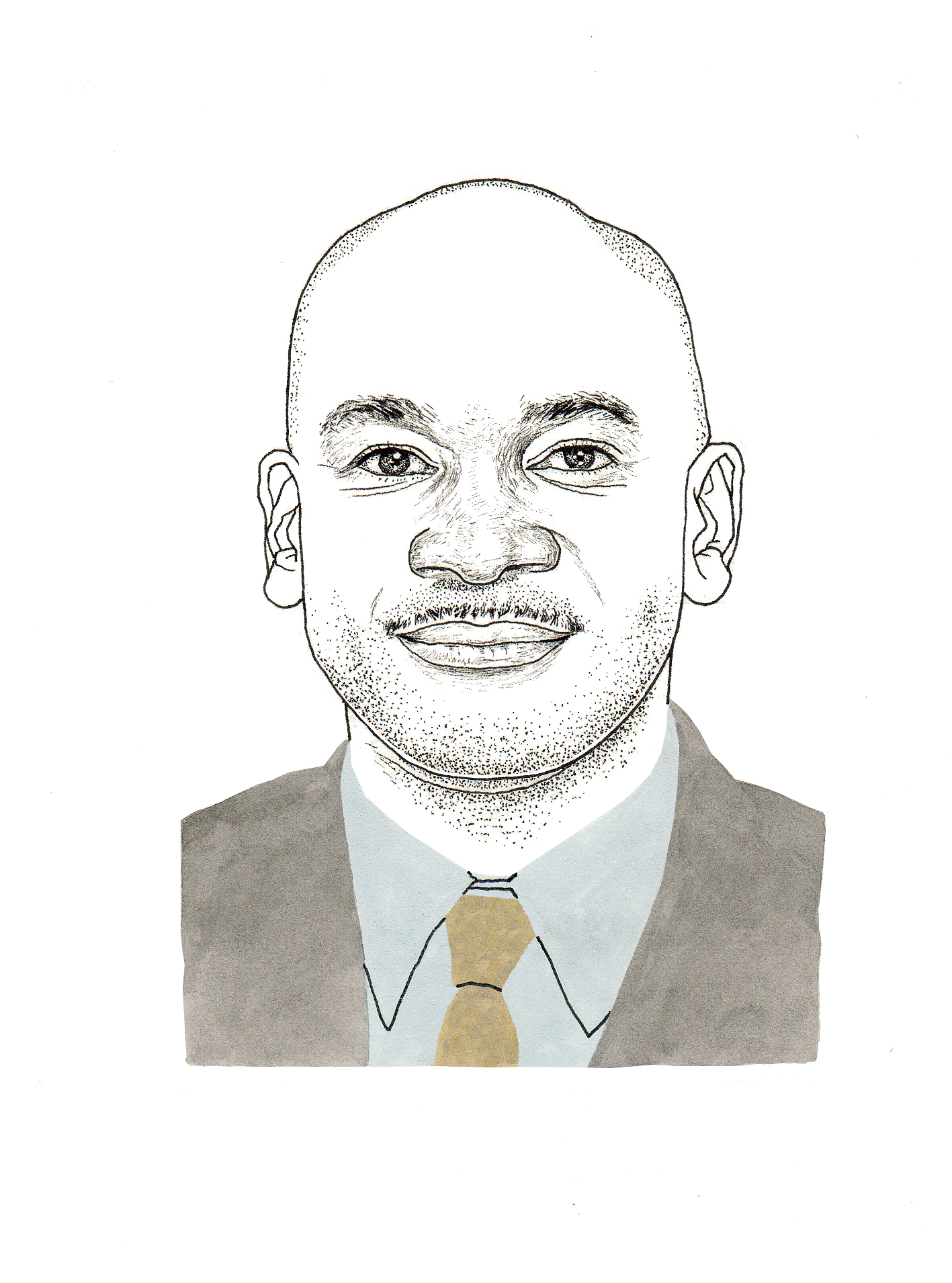

In November 2012, the heads of four leadership programs at Teachers College – Brian K. Perkins, of the Urban Education Leaders Program (and former President of the New Haven, Connecticut, Board of Education); Pearl Rock Kane, of the Klingenstein Center for Independent School Leadership; Eric Nadelstern, of the Summer Principals Academy (and former Deputy Chancellor of the New York City school system); and Nora Heaphy, of the Cahn Fellows Program for Distinguished Principals – gathered to talk for this report about what it takes to lead and succeed at a K–12 school.

What do you see as essential in K–12 school leadership?

NADELSTERN: For many years, school districts focused more on school management than on instructional leadership. The biggest change in recent years is selecting principals from among our best teachers and ensuring that principals understand that their primary role is instructional leadership.

KANE: I agree, but I also think we must develop teachers continually and not just hire them to be autonomous in the classroom. We need teachers who work together, who develop a culture of continual improvement and who can be motivated by colleagues to continually improve their craft.

PERKINS: I teach a course in the TC Summer Principals Academy titled School Leadership. One of our students said, “I don’t know what the real indicator is that I’m being a good leader.” And I said, “Well, turn around and look. If no one’s following, you’re not a leader.” Leadership involves being able to motivate people to do the things that you need and want them to do.

NADELSTERN: I’d go one step further and say that these days, with the focus on student outputs rather than faculty inputs, effective school leaders produce significant results.

HEAPHY: And I would add that thinking strategically and systemically about change is the height of leadership. And that takes a whole different set of skills in some cases. It means motivating people, motivating your followers, many of whom you don’t have formal authority over. Transformational leadership is the key lever at this point, particularly in public schools.

Instructional leadership would seem to require having once been a teacher. What about the notion that the person best equipped to lead isn’t necessarily the one who is most skilled at the main thing the organization does – that there’s something else called leadership?

NADELSTERN: It’s different for district leaders. The role of chancellor, for instance, in urban districts is a managerial and political position, and you don’t necessarily make your best teachers a chancellor. However, teaching is leadership, and the difference between a teacher and a principal is who the students are. The teachers teach children, the principal teaches teachers. Which is why I think the best classroom leaders should ultimately be tapped to become building leaders.

PERKINS: I certainly believe that principals should be instructional leaders. But we can’t lose the managerial component; principals have to have a command of the entire game. So they really need to serve in a coaching capacity. A lot of recent research suggests that good coaches are far more likely to get more out of their colleagues in classrooms.

NADELSTERN: But if you don’t start with outstanding teachers, you’re not likely to wind up with great coaches.

HEAPHY: When I reflect on my own leadership trajectory, I find that the transformative moment was moving from being someone who just got everything done, to distributing leadership throughout the organization. It’s a delicate balance between maintaining a certain amount of control as a leader and relinquishing that control. And that only comes from time in the job – from developing a certain savvy that doesn’t necessarily come from the classroom.

KANE: You realize that sharing power increases power, that it isn’t a zero-sum game when you give away some of your job and hold people accountable. The other part, I think, is having a vision of what is possible in the school and communicating that vision in everything you do.

Eric, you suggested that school leaders are accountable for student outcomes, which wasn’t true even a decade ago. How has this changed the game?

NADELSTERN: It’s setting up conflicts at every level of public education and public service, because we’re not accustomed to accountability, and not just in education. I was in the New York City public schools for 39 years, and during most of that time, teachers, principals, superintendents and even chancellors did not lose their jobs because kids weren’t learning. But two years is a long time in the life of a child. And if a leader can’t move a school in two years, the system shouldn’t hesitate to replace that person with someone who can.

KANE: It used to be that schools were evaluated on compliance, on inputs, and now we’re pleased to see that schools are being measured by outcomes. And we have examples of schools that are successful in educating poor students. That has made a difference in showing what is possible.

PERKINS: But we have not yet been able to bring to scale those models that are working. There are examples of success that we might have in one or two schools in depressed areas, but not in others. We have to look closely at these pockets of success, and I think that is where leadership plays an important role.

Do school leaders have to be heroes to succeed nowadays? Or is ordinary competence enough?

HEAPHY: I’m of the mindset that leadership can be learned. I visited a school led by a current Cahn Fellow who has made his institution very high-performing thanks to his understanding that the entire school is a living system. He knows that if he wants to create change he has to pay attention to every component, from the hiring and induction of teachers to a very careful and intentional process of developing those teachers over time. A culture comes out of that, one of high performance and expectations of excellence. If a teacher who comes into that building is not a good fit, the culture pushes them out. This ability to look at the system as a living organism is a skill that can be learned. People aren’t just born with it, and you don’t have to be a heroic leader to create that.

PERKINS: You don’t have to be heroic. But exceptional, yes. In terms of where public education is now, we need exceptional individuals to be in classrooms and front offices, and until we stop saying that everyone can teach, that anyone can do this who tries, we’re not going to get the results we need.

KANE: Teaching is a very demanding role, as is leadership. It probably is one of the hardest things that people choose to do in life. I agree that thinking anyone can do it is mistaken.

NADELSTERN: Part of the reason success presents as heroism is that most districts and schools don’t have the incentives right. If you demonstrate success, you’re given a harder job. If you’re a successful teacher, you’re given the most challenging students. If you’re a successful principal, we send you to another school that’s remarkably troubled. We exact consequences for success and reward failure. In New York City, 40 percent of the principal’s day is spent responding to requests from central. That’s typical for large urban school districts. In that context, to be a successful principal does require a degree of heroism.

Do leaders of independent schools have an advantage when it comes to communicating a culture?

KANE: Certainly having resources matters. It allows for greater latitude to determine practices. It matters to have facilities that communicate how one feels about the importance of children in society. That helps to shape

a culture where we can enforce high expectations for students and teachers. Mission is also important in independent schools, and schools can recruit faculty and families that subscribe to the mission. This helps to strengthen the culture.

NADELSTERN: I’d like to see all schools become independent schools. The structure of large urban school districts ought to be independent schools that choose to come together and network around the issues of providing each other support and common accountability.

PERKINS: Some of our best examples of success in public schools are, in fact, where

the district provides the resources, provides the latitude to make some choices, and gets out of the way.

How do you help someone self-assess to become a better leader?

HEAPHY: A key that I look for when I visit schools and talk to current Cahn Fellows is this idea of coaching and distributive leadership, which I think separates good leaders from great leaders. It’s the ability to provide specific, productive coaching to improve student learning outcomes, and also to coach teachers to take on more leadership in the school.

NADELSTERN: I would want a principal to be able to describe a continuum of teacher development and tell me where each of her teachers plots out on that continuum, and what she’s doing to move that person to the next level. It’s what we expect from classroom teachers relative to their students, and it’s what we ought to expect of principals relative to their teachers.

KANE: My first question would be, “What are the objectives of your job?” And if there aren’t clear objectives, then develop important objectives that would lead to student learning. And then based on that, we should set up criteria for evaluating how we know when we get there. I tell students, when they get a job that seems nebulous, to discuss with administrators what success would look like in the job and use that as a guide in setting up evaluation criteria.

What are the most frustrating, intractable challenges for a school leader?

PERKINS: One would be removing unproductive staff, and not just teachers – the ability to move people out of the organization who don’t fit.

NADELSTERN: Fear of change is a big one. Schools, above all organizations, need to be learning organizations where you’re constantly learning about what’s working and channeling it back, not just into better practice but also into different structures to support that practice. So, schools ought to be continually changing organizations, and yet most people are fearful of change. And so how do you get people comfortable with that? To accomplish that, the leader needs to be the lead learner.

HEAPHY: As a practical matter, you have the new APPR [annual professional performance review] systems and protocols for teacher and principal evaluations. How the states and districts and individual school leaders and individual teachers are going to measure growth of their students, and how they’re going to be evaluated based on that growth, is just mind-boggling to me. It’s going to have rippling effects throughout the system for years to come, and that’s something that school leaders are really going to have to grapple with.

KANE: In private schools, the challenges are financial, for now and in the future. I’ve talked about small classes and good facilities, but all that has a cost. Many middle-class families are being squeezed out of the private-school market because they simply can’t afford it. So, figuring out how to make tuition affordable is one of the greatest challenges. The other challenge is preparing students to thrive in a world that is diverse in terms of race and ethnicity. Private schools can accomplish this by setting up intentional communities that are diverse in terms of faculty and students. They also have to confront the financial challenge of recruiting families of different socioeconomic levels. Financial aid is a great challenge that schools have to contend with if they aim to be truly diverse.

Published Thursday, Feb. 14, 2013