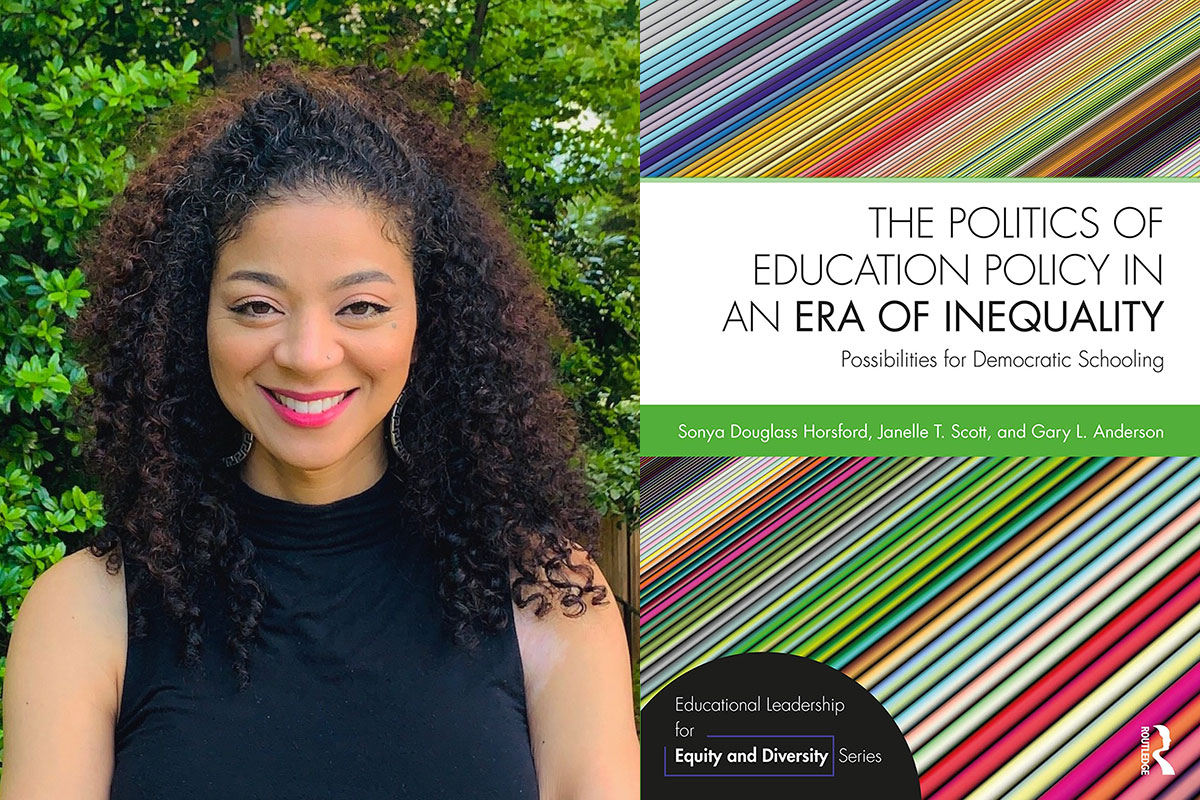

The Politics of Education Policy in an Era of Inequality: Possibilities for Democratic Schooling, co-authored by Teachers College’s Sonya Douglass Horsford, Associate Professor of Education Leadership and Founding Director of TC’s Black Education Research Collective (BERC), often feels as though it is speaking directly to the COVID pandemic and its impact on America’s school system.

In fact, the book was published in 2019 — but it seems no accident that a text with profound insights into how the politics of reform and competition in K-12 education have worsened school inequality has been recognized by the American Educational Studies Association with one of its coveted Critics’ Choice Book Awards for 2020.

Horsford and her collaborators — Janelle T. Scott of the Graduate School of Education at the University of California at Berkeley, and Gary L. Anderson of the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, New York University — employ critical policy analysis, an approach that spotlights connections between education and relations of dominance and subordination in the larger society. They focus on how “dismantling the government’s role in education limits the democratic possibilities of schooling.” They trace how market-driven approaches to education reform have ensured that “teachers, administrators, and students will be more mobile, leading to less stability and a weakening of professional expertise and organizational capacity.” They demonstrate that “a new generation of teachers and administrators is being socialized into a very different workplace with a different conception of teaching and leading.” And they lament a diminished faith in public education and the government’s ability to administer it, concluding that “when the market and private sector take over the role of the State or powerful corporations have inordinate power over the State, then citizens can no longer participate in a robust political democracy, but rather become resigned and passive consumers.”

IT LAUNCHED MORE THAN A SPACE RACE Horsford's book links America’s Sputnik-era fears of falling behind in global competitiveness to a resulting narrower conception of schooling. (Photo: Smithsonian.edu)

Horsford and her co-authors look back to America’s Sputnik-era fears of falling behind in global competitiveness in science and economic development. That reactive thinking, they argue, shaped a narrower conception of schooling. The result, today, is that “record levels of economic inequality and reduced social mobility amid widening and deepening class divides present tremendous challenges for school district leaders and education advocates committed to ensuring equality of educational opportunity for all students.”

When the market and private sector take over the role of the State or powerful corporations have inordinate power over the State, then citizens can no longer participate in a robust political democracy but rather become resigned and passive consumers.

The United States isn’t alone in wrestling with these challenges. Horsford, Scott and Anderson point to a similar dismantling of education as an institution for the public good in Chile, Australia, India and other countries, where, with similar “laser-like focus on producing human capital for international competition, schools are largely abdicating their responsibility to educate a new generation to defend democratic principles.”

Exploring “a new vision for leading schools grounded in culturally relevant advocacy and social justice theories,” the book tells the story of how education policy has come to focus on markets, privatization, the expansion of charters and vouchers, and the training of a new class of “professionalized” and “managerialized” principals who are so hamstrung by “accountability” that they are unable to focus on their schools as humanistic institutions that nurture individuality, creativity and independent thinking.

A central thesis of the book is that although principals and district leaders have become divorced from a policymaking process that is now largely in the hands of politicians, philanthropists, think tanks and school reform organizations, they are essential to any efforts to create and sustain a system of education that does not treat students differently based on their race, culture, or zip code.

A limited focus on preparing school and district leaders for the politics of education and education policy not only undermines their ability to be effective administrators, but also to demonstrate the leadership capacity, political awareness, and advocacy central to leadership for social justice.

The authors offer critical policy analysis as a framework for change. On one level they advocate for the building of bridges between policymakers and practitioners. But they also argue for instilling greater political savvy and a sense of realpolitik among education leaders:

“A limited focus on preparing school and district leaders for the politics of education and education policy not only undermines their ability to be effective administrators, but also to demonstrate the leadership capacity, political awareness, and advocacy central to leadership for social justice.”

In their preface, Horsford, Scott and Anderson state that their goal is “to sound the alarm that that our public schools and our democracy are being diminished” — and they quote the journalist David Wallace Wells’ assertion (made about climate change) that “no matter how well-informed you are, you are surely not alarmed enough.”

Before you burrow under the covers and toss this book out the window, we want to be clear that we don’t see everything as gloom and doom. We are witnessing broad-based mobilizations around the world to defend democratic principles.

But, they also tell their readers, “before you burrow under the covers and toss this book out the window, we want to be clear that we don’t see everything as gloom and doom. We are witnessing broad-based mobilizations around the world to defend democratic principles.” Ultimately, their book, which includes descriptions of school leaders whom the authors consider exemplary “democratic professionals” and offers discussion sections after each chapter, is a practical guide for how to build on such work.

“This is a difficult time to be an educator if you view your job as keeping your head down and allowing reformers who are mostly non-educators to define you professionally,” they write “But if you are committed to your students and their families and communities, and are willing to struggle to change policies and practices inside schools and join with those trying to make changes outside of schools, than these are exciting times to be an educator.”